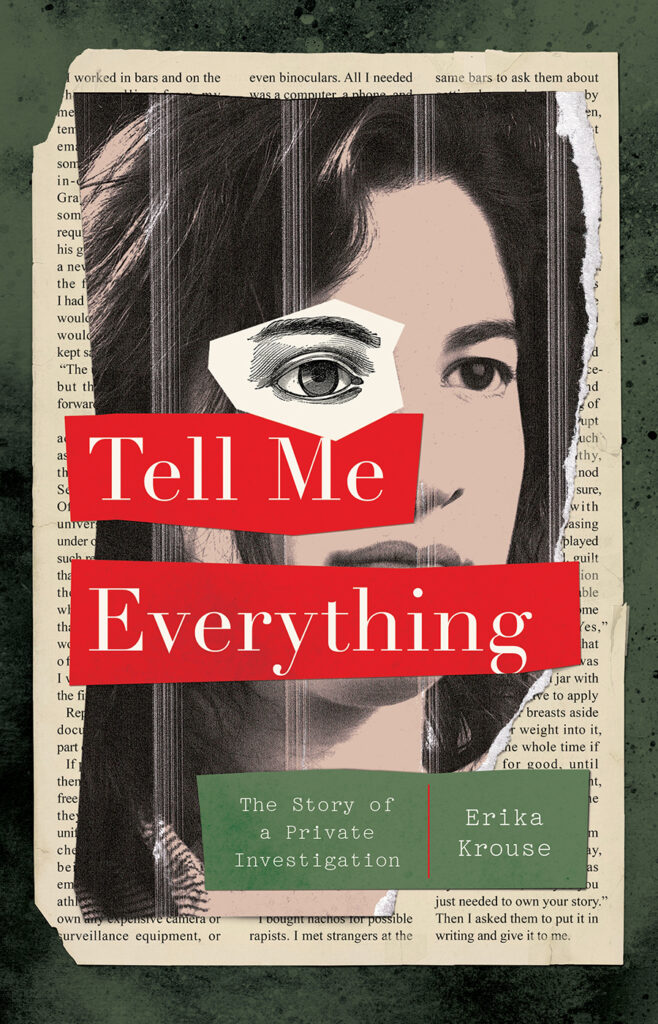

Erika Krouse has one of those faces that leads people to tell her everything, she says. It even turns into a job opportunity as a private investigator, and she soon ends up uncovering the truth on one of the biggest national scandals to hit Colorado’s flagship university. If you haven’t read this book yet, you should!

Part memoir and part literary true crime, Tell Me Everything is the mesmerizing story of a landmark sexual assault investigation and the private investigator who helped crack it open. Ross Investigators spent some time asking Erika for her insight into private investigations and advice for others in the business.

Q: What is most effective for getting people to open up to you? Especially for those who maybe don’t have the approachable face?

A: I think it’s kind of like jazz and you have to play off what you’re given. That said, I believe it’s important to come with a baseline of empathy, respect, and a clearly stated agenda. For example, it usually worked for me to say, “This is what I’m looking for, here’s why, and I understand why this may be difficult for you to talk about. I tried a lot of techniques—silence, mirroring, getting them to mirror you, disruption, and lots of cool forms of questioning. But my favorite thing was to follow what I thought of as “conversational snags”—I don’t know what they’re really called. It’s about how, when people talk, they lead you in a certain conversational direction, but any deeper unsaid stuff leaves behind these mid-sentence barbs or hooks that snag on the conversation a little bit.

For example, a witness might answer a question by saying, “Diane and I don’t really talk anymore, but back then she told me X, Y, and Z.” The witness wants to talk about X, Y, and Z, and if that’s the information I want, I’ll follow. But then if I eventually circle back to the snag and ask, “Why don’t you and Diane talk anymore?” the witness may open up with something important, just because she’s grateful that I paid attention. And witnesses who are deceptive or withholding tend to leave more of those snags, because most people really want to tell the truth despite everything. If there are too many snags to remember, I’d write them in my notes and return to them whenever we hit a flat place in the conversation. Too many times I’d realize in the middle of the night that I forgot to circle back to one of these things. But it can be an excuse to call them later: “You know, when we talked, you said something that’s stuck in my head ever since…”

Q: In the book, you mention the tricks you used and that you manipulated people to get the information you needed – what advice do you have for private investigators s on how to navigate these kinds of scenarios that perhaps conflict with their own morals vs. getting the info they need?

A: That’s something I never figured out, how to navigate my moral quandaries, and it’s why I had to write Tell Me Everything. It’s also why I had to pause PI work and figure myself out. It did help that I believed in the cases themselves and which side I was working for. It also helped when I started playing the longer game—beyond seeking information, I tried to recruit allies who were motivated to get involved. That helped with the morality of it, because they had a choice. Sometimes the situation was so bad or dangerous that people paid a price for giving us leads. So if they believed in the case, too, they were making their own ethical decision to help, despite the possible risks.

Q: Are there signals for when a PI is reaching a level of discomfort that’s too much?

A: You can ask, right? You can say, “You seem uncomfortable. Was that question rude? I’m so sorry.” Being vulnerable yourself can help—saying you’re nervous or that the case is personal to you. Quid pro quo helps. Apologies help, and making amends. Alcohol helps, and so does food, especially if you’re paying.

If none of that worked and someone completely shut down, I just tried to change the mood in any way I could think of: I stuttered, surprised them with a weird guess about them, spilled on myself, asked questions about someone they loved, gave them an important piece of information, had a coughing fit, or sometimes just went to the bathroom to give them space. You can probably tell from all these answers that I’ve screwed up quite a lot. I think it’s hard to avoid crossing lines because that’s your job. I was more successful maintaining rapport when I was able to leave my ego and personality out of the encounter, so I had more emotional space to notice their boundaries. I think it was Will Rogers who said, “Never miss a good chance to shut up.”

Q: What helped keep you going in your career as a PI? What, if anything, would you change if you could?

A: Some of my mistakes hurt people, so I would change those actions for sure. I would also use better organizational systems, which I only put in place later. As for what kept me going, I was really motivated by the cases themselves. They were interesting and complex and dynamic and controversial. I also loved learning about the job, ways to do it better. Each interview had completely different psychological and strategic challenges, and I was always adjusting on the fly. Where else can you practice this stuff but on the job?

Q: Are there other coping mechanisms that might help private investigators when dealing with frustrating aspects of a case?

A: It’s easy to question what you’re doing and why. There are so many dead ends and dilemmas. When I hit a dead end, I usually backtrack and re-interviewed people, or tried people I couldn’t reach before, or looked for a different category of people that I should consider. I’d talk through the different angles of the case, asking and re-asking myself who, what, when, where, how, and why. I’d ask myself what bothered me about the case, to see if I had blown past something out of discomfort. I made charts, did things with index cards or sticky notes or butcher paper, or drew timelines. Something usually shook loose. And I wasn’t going to give up unless I discovered I was wrong about the ethics of the case. Attorneys generally don’t get to abandon their clients when they discover they’re terrible, but PI’s can walk away from someone who turns out to be in the wrong.

Q: Is there anything PIs can ask of their clients that would help them do their job better? On the flip side, what suggestions do you have for what attorneys (or other clients) can share that will help the PIs do their job better?

A: Give us correct names, and correct spellings of names! Gah, I lost too many hours to that problem. If a client or lawyer gives their PI the leeway to form their own strategy, that can really help, because we’re creative people. Too many attorneys believe that they’re smarter than their PIs, and only give them simpler tasks like skip tracing, but we’re capable of so much more. We’re good at puzzles, so give us the puzzles! Tell us what you’re trying to prove, or share your entire legal argument with us so we can get creative about what to look for. Tell us everything that’s happening with the case as it happens, so we don’t do redundant work. Also, laugh at our jokes. We’re very funny people.

Q: Any other advice for PIs or people considering a career as a PI?

A: I think it’s a good idea to first assess how cynical you are, and if you can handle difficult stuff. I tended to score complicated cases, so each case felt like I was reaching into a black box. I couldn’t do a good job if I flinched from what I found. Sometimes it’s just too much, like when I was asked to investigate a child pornography case; I just didn’t have what it takes to do it. I think it’s important to respect your limits, so you can have a long career. It’s good to feel like you’re making the world better, but not at the expense of your soul.